Cool Biz: Energy Conservation Efforts in Japan

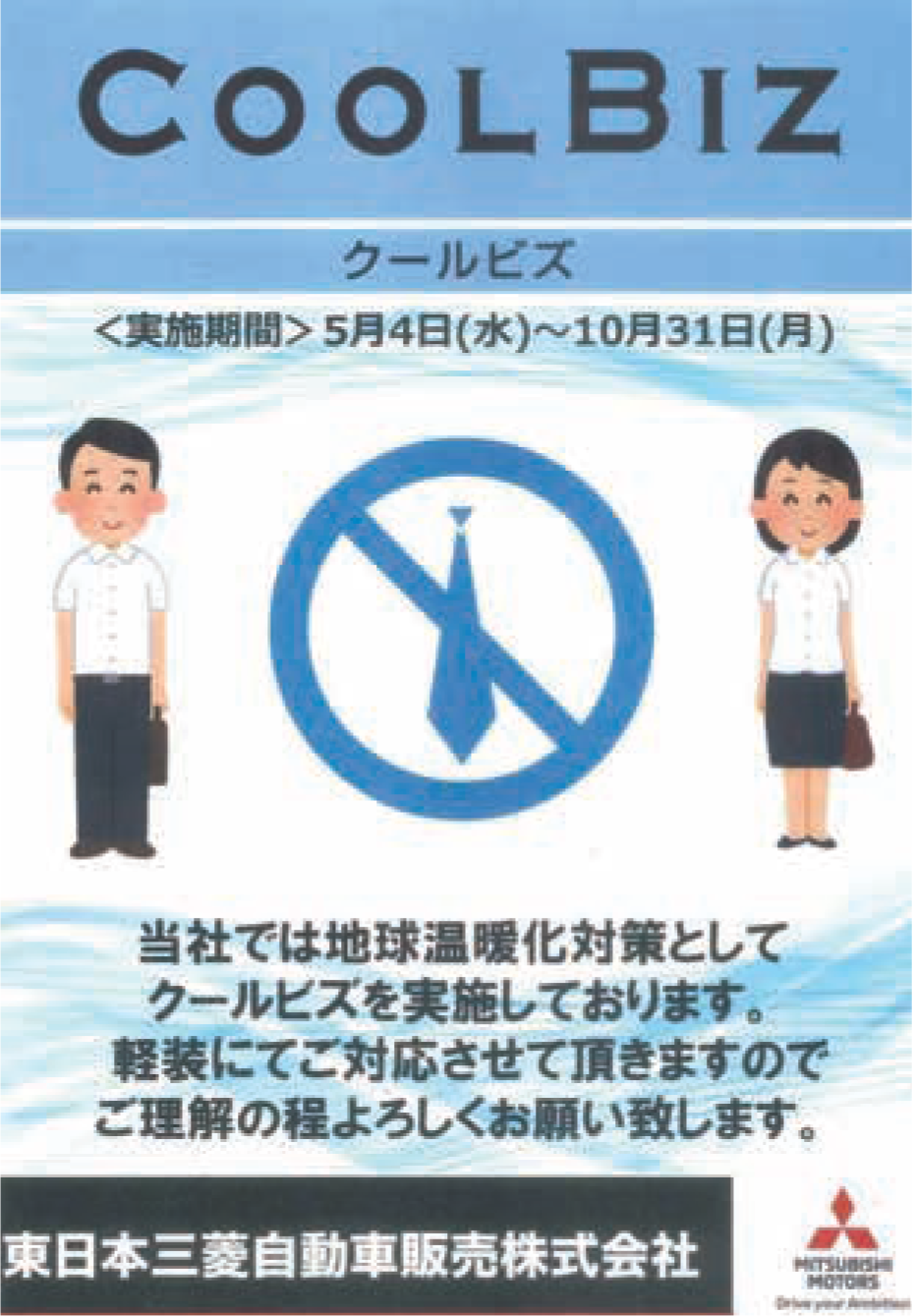

The Cool Biz initiative, which originated in Japan during the summer of 2005, was introduced by the Ministry of the Environment as a strategy to reduce domestic electricity consumption by minimizing the reliance on air conditioning systems.

Cool Biz: Energy Conservation Efforts in Japan

The Cool Biz initiative, which originated in Japan during the summer of 2005, was introduced by the Ministry of the Environment as a strategy to reduce domestic electricity consumption by minimizing the reliance on air conditioning systems. This endeavor involved a pivotal alteration to the standard office air conditioner temperature, setting it to 28°C (approximately 82°F), and implementing a more relaxed summer dress code within the Japanese government bureaucracy. This allowed government staff to work comfortably in warmer conditions, ultimately paving the way for the campaign's subsequent adoption by the private sector.

The concept was initially proposed by Yuriko Koike, who served as the Minister at that time, within the administration of Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. Notably, all government leaders actively participated in the Cool Biz initiative. Prime Minister Koizumi, in particular, frequently appeared in public without wearing a tie or jacket, significantly increasing the visibility and impact of the campaign.

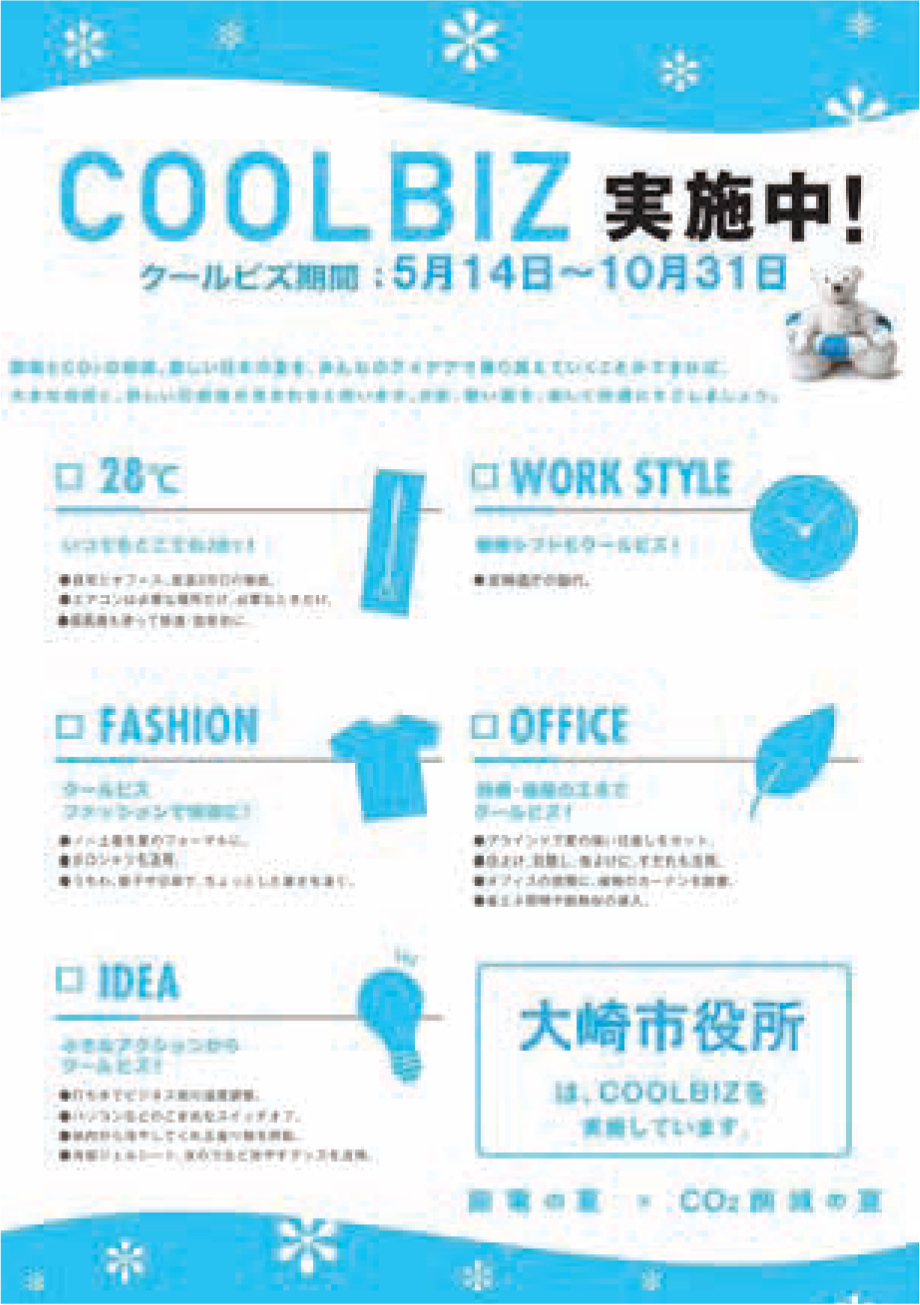

The Ministry of the Environment (MOE) directed central government ministries to maintain air conditioner temperatures at 28°C throughout the campaign's duration. Originally scheduled from June to September, the campaign was extended starting in 2011, following electricity shortages resulting from the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. As of now, the Cool Biz campaign spans from May to October each year.

The Cool Biz dress code recommendations include starching collars to keep them upright for better comfort, opting for trousers made from breathable and

By Ryan Chang

moisture-absorbent materials, and encouraging the use of short-sleeved shirts without jackets or ties. However, there was some initial confusion among workers about adhering to the new business casual guidelines. Many employees initially arrived at work with jackets in hand and ties in their pockets. Some government workers even expressed concerns about the perceived impoliteness of not wearing a tie when meeting counterparts from the private sector.

Interestingly, some private companies, such as Toyota and Mitsubishi Motors, went a step further by explicitly instructing their employees not to wear jackets and ties, even during business meetings with partners.

On October 28, 2005, the Ministry of the Environment (MOE) released the findings of an assessment of the Cool Biz campaign's impact. The MOE had conducted a web-based questionnaire survey on September 30, 2005, involving approximately 1,200 individuals randomly selected from an internet panel assembled by a research company. According to the survey results, a noteworthy 95.8 percent of respondents were aware of the Cool Biz initiative, with 32.7 percent reporting that their workplaces had raised the air conditioner thermostat settings compared to previous years. Based on these statistics, the Ministry estimated that the campaign had led to a reduction of approximately 460,000 tons of CO2 emissions—equivalent to the emissions produced by approximately 1 million households for a month.

In 2006, the results of the campaign showed even more promising outcomes, resulting in an estimated reduction of 1.14 million tons in CO2 emissions, equivalent to the emissions from around 2.5 million households for a month. The Ministry expressed its commitment to persistently promote the practice of maintaining office temperatures no lower than 28°C during the summer, with the ultimate goal of ingraining the Cool Biz concept firmly into society.

Subsequently, in July 2009, the Cabinet Office unveiled the results of a new questionnaire survey. This survey indicated that 91.8 percent of respondents were familiar with the Cool Biz campaign, and an impressive 57 percent of them had actively implemented the campaign's principles in their daily lives.

Additionally, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) analyzed that the Cool Biz campaign increased replacement demand for clothing and generated positive macroeconomic effects on the GDP by 18 billion yen for summer 2005. Dai-Ichi Life Research Institute announced that the total economic effect was more than 100 billion yen in 2005.

Beyond Cool Biz

Following the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in March 2011, the shutdown of many nuclear power plants for safety reasons led to energy shortages. The government announced the new Super Cool Biz Campaign in response to power shortages and the need to conserve energy usage by at least 15 percent.

The Super Cool Biz Campaign built upon the Cool Biz campaign, suggesting guidelines to help reduce energy use both at work and at home. To further conserve energy, the government also requested switching off computers not in use, called for shifting work hours to the morning, and taking more summer vacation than usual.

The government further loosened the Cool Biz summer dress code in the name of Super Cool Biz. The government launched a Super Cool Biz casual dress code campaign to encourage government and private company workers to wear outfits appropriate for the of-

Japanese Government Cool Biz Summer Dress Code

Not required to wear:

- Necktie

- Jacket

- Long-sleeve shirts

Allowed to wear:

- Half-sleeve dress shirts

- Kariyushi shirts (Okinawan Aloha shirt)

- Polo shirts

- Hawaiian shirts/Aloha shirts

- Chino pants (lightweight material, typically cotton, like khakis)

- Sneakers

Not allowed to wear:

- Exercise shirts

- Shorts

- T-shirts

- Jeans

fice yet cool enough to endure the summer heat. Polo shirts and business casual wear were allowed, while jeans and sandals were also acceptable under certain circumstances.

June 1 marked the start of the Ministry of the Environment's Super Cool Biz campaign, with “full-page newspaper ads and photos of ministry workers smiling rather self-consciously at their desks wearing polo shirts and colorful Okinawa Kariyushi (Aloha) shirts." The Super Cool Biz campaign was again repeated in 2012.

What exactly does Cool Biz and Super Cool Biz mean for those of us working in Japan? Depending on your company, the answer could be anything from cooperating with drastic energy-saving measures, or nothing very noticeable at all. However, many Japanese companies are taking the government guidelines seriously and reducing their energy consumption by asking their employees to enthusiastically comply. The Cool Biz campaign is still used to this day to curb energy consumption and reduce the risk of overloading the power grid, although participation is not mandatory.

The success of Cool Biz in Japan has since extended to other geographic locations, as well. The South Korean Ministry of Environment and the British Trades Union Congress have promoted their own Cool Biz campaigns since summer 2006, while the United Nations was inspired to launch the "Cool UN" initiative in 2008.

Within Japan, retrocommissioning has played a significant role in complementing the Cool Biz energy campaign, contributing to broader energy conservation efforts across the country. As building energy performance reporting became mandatory under the Energy Conservation Law in 2006 (right around the same time Cool Biz was launched), the popularity of commissioning new buildings in the construction phase gained popularity, as well. When combined with the Cool Biz campaign's emphasis on relaxed dress codes and higher thermostat settings, both retrocom-missioning existing buildings and commissioning new buildings can add another layer of energy conservation, contributing to a more sustainable and environmentally friendly approach to cooling buildings and reducing the carbon footprint on a larger scale.