Recognizing the socio-technical opportunity of workplace: An analysis of early responses to COVID-19.

COVID-19 has disrupted the ways in which we work, offering an opportunity to rethink our workplaces. Organizations have had to adapt and respond in unprecedented ways to enable continued organizational performance that have come to see many people working from home. Early responses to ‘return-to-work’ have sought to repurpose existing workspace arrangements, but they miss the unique opportunity to reconceive ‘workplace’ more comprehensively, as well as the role the property community has in enabling work. This paper aims to highlight the opportunity of viewing the workplace holistically through the lens of socio-technical systems. An examination of the early responses to the pandemic identified a focus on the technical aspects of reoccupying workspaces, but taking from socio-technical systems, this should not be to the detriment of other factors. A more nuanced debate regarding who should return to work and how this will occur is presented, which highlights further a need to move beyond the physical workspace and to reflect on how we can enable ways of working.

Corporate Real Estate Journal Volume 10 Number 1

Recognising the socio-technical opportunity of workplace: An analysis of early responses to COVID-19

Received (in revised form): 26th June, 2020

Chris Moriarty*

Director, Institute of Workplace and Facilities Management, UK

Matthew Tucker**

Reader, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

Ian Ellison†

Co-founder, 3edges Workplace Ltd, UK

James Pinder††

Co-founder, 3edges Workplace Ltd, UK

Hannah Wilson‡

Senior Lecturer, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

Chris Moriarty is director of insight at the Institute of Workplace and Facilities Management (IWFM). Previously he was managing director at Leesman, the world’s leading assessor of workplace effectiveness, where he was responsible for the creative and strategic development of the Leesman brand in the UK and internationally. Chris has extensive professional body experience as well as a track record in delivering industry-wide thought leadership and policy campaigns on top of strategic marketing and sales experience. Prior to his first spell at BIFM as head of insight and corporate affairs, where he worked to establish the Institute as the voice of the sector, he was head of corporate affairs at the Chartered Institute of Marketing.

Matthew Tucker is a reader in workplace and facilities management at Liverpool Business School, Liverpool John Moores University. He

is an acclaimed author, publishing papers in internationally recognised journals, books and reports, and is currently the associate editor for Facilities (Emerald Publications). International roles include being an independent expert for the BSI Facilities Management Technical Committee (FMW/1) and past research chair for the European Facilities Management Network (EuroFM). Matthew is a Fulbright Scholar, winning the first-ever RICS-Fulbright award, developing crucial research on customer performance measurement in FM. He is a certified member of the Institute of Workplace and Facilities Management (CIWFM), a member of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (MRICS) and a Chartered Facilities Management Surveyor.

Ian Ellison co-founded 3edges to help people think differently about the organisational value of

†Tel: 07595 933219; E-mail: ian.ellison@3edges.co.uk

††Tel: 07931 579056; E-mail: james.pindar@3edges.co.uk

‡Tel: 0151 231 8130; E-mail: h.k.wilson@ljmu.ac.uk

Corporate Real Estate Journal Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 51–62 © Henry Stewart Publications, 2043–9148

workplace. With 20 years’ experience spanning workplace and facilities management practice and education, Ian has developed a reputation as an engaging facilitator and provocative speaker. He is passionate about the power of workplace to enable better business outcomes. Ian is co-founder and host of the Workplace Matters podcast and was also a key contributor to the ()Stoddart Review. Particularly interested in change leadership and workplace challenges within organisations, Ian has been involved in a range of commissions to help facilitate organisational performance improvement. Ian has published journal articles, papers and book chapters on a range of FM and workplace topics.

James Pinder is a consultant, researcher and educator with a longstanding interest in workplaces and the impact that they have on people and organisations. He is a skilled and experienced researcher and evaluator and has delivered workplace consultancy for a range of clients. James is very experienced at designing and undertaking complex research evaluations involving both qualitative and quantitative datasets. He has published widely, in both academic and practitioner-focused publications, and is particularly adept at providing clients with new insights and communicating those insights to people in ways that are engaging and easy to understand.

Hannah Wilson is a senior lecturer in research methods at Liverpool Business School, Liverpool John Moores University. Hannah undertook her degree in applied psychology and then went on to complete her PhD investigating the impact of learning environments in 2017. There are three strands to her expertise, workplace strategy, pedagogy and work psychology, which are fundamentally related to adaptations that can be made to improve individuals’ experiences and health within the work environment. Some of her current projects include examining productive workplaces, coping strategies of project managers for dealing with difficult situations, and teaching and learning on DBA programmes.

She also has an expertise in research methods teaching and experience in conducting research utilising both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. Hannah would welcome connections with those with overlapping interests, from both academia and industry.

AbstrAct

COVID-19 has disrupted the ways in which we work, offering an opportunity to rethink our workplaces. Organisations have had to adapt and respond in unprecedented ways to enable continued organisational performance that have come to see many people working from home. Early responses to ‘return-to-work’ have sought to repurpose existing workspace arrangements, but they miss the unique opportunity to reconceive ‘workplace’ more comprehensively, as well as the role the property community has in enabling work. This paper aims to highlight the opportunity of viewing workplace holistically through the lens of socio-technical systems. An examination of the early responses to the pandemic identified a focus on the technical aspects of reoccupying workspaces, but taking from socio-technical systems, this should not be to the detriment of other factors. A more nuanced debate regarding who should return to work and how this will occur is presented, which highlights further a need to move beyond the physical workspace and to reflect on how we can enable ways of working.

Keywords: COVID-19, coronavirus, pandemic, built environment, facility/ facilities management (FM), socio-technical systems, workspace, workplace

INTRODUCTION

As with any major social, political and economic upheaval, the COVID-19 pandemic has sometimes revealed uncomfortable truths about the societies we live in, but it also provides us with an opportunity to question, challenge and rethink the way things should be done going forward.

Arguably some of the most striking examples of this ‘rethinking’ have been about

the workplace. The pandemic has forced organisations to rethink their physical and virtual workspaces and grapple with their deep-rooted work cultures, and it has put a spotlight on people doing jobs that were previously taken for granted or overlooked.

1

1

It was contended at least two decades ago that ‘work is no longer a place — it is an activity that can be conducted anywhere’.This has never been more pertinent for office-based workers as the pandemic we are currently experiencing has also given rise to a large-scale, and largely involuntary, ‘experiment’ in homeworking. With many workers being forced to work from home during lockdown and to renegotiate their work–life boundaries, there has been a flurry of opinion about what this might mean for the way organisations will work in future and what implications this will have for the workplace.

Organisations that have previously been slow to implement ‘flexible working’ arrangements (or have been opposed to them) have had little choice but to let their employees work remotely and more autonomously. When the old rules no longer apply, organisations have had to embrace the art of the possible and come up with solutions to enable their employees to continue working.

For instance, information technology (IT) solutions that would normally take months to implement have been rolled out in a matter of days. Having seen how their staff can work more flexibly, some business leaders have begun to consider whether homeworking can become more commonplace, and therefore whether their organisations will require less, or perhaps different, workspace going forward.

At the time of writing, it is too early to tell, meaningfully, how effective the homeworking ‘experiment’ has been for many organisations, and what the medium and long-term implications will be for built environment industries specifically (including, for example, corporate real estate [CRE],

facilities management [FM] services) or the economy more generally. The way in which the built environment industry has responded to the crisis has, however, been revealing.

2

2

This paper considers an analysis of early responses, both from the built environment industry as well as business leading examples from other sectors, and then discusses the implications in terms of Trist and Balmforth’s notion of socio-technical systems.

It suggests that, by focusing almost wholly on technical aspects, the built environment industry fails to recognise the opportunity to demonstrate organisational value beyond making buildings and workspaces ‘COVID secure’.

3

3

This is hardly surprising given the evolution of the sector and, more specifically, the FM profession over the last 40 years. The paper observes how FM has moved away from a heritage in what early pioneers outlined as ‘expert workplace management’,which recognises workplaces as the social and distributed rather than purely physical spaces where people use the tools available to them to get their work done.

4

4

The COVID-19 pandemic may offer a ‘make-or-break’ moment for FM, and those claiming workplace expertise, to reprise and develop a genuine workplace contribution. This would necessarily require changes in knowledge, skills and behaviour. Otherwise, post-pandemic, much of the built environment industry risks becoming sidelined and undervalued, as many within the facilities management profession feel they are today.

It would be beyond disappointing to look back and acknowledge a failure to act on the opportunity. The paper therefore concludes with some suggestions toward ongoing organisational relevance.

EARLY RESPONSES TO COVID-19

Amid evolving government advice regarding working arrangements, and the imminent

5

5

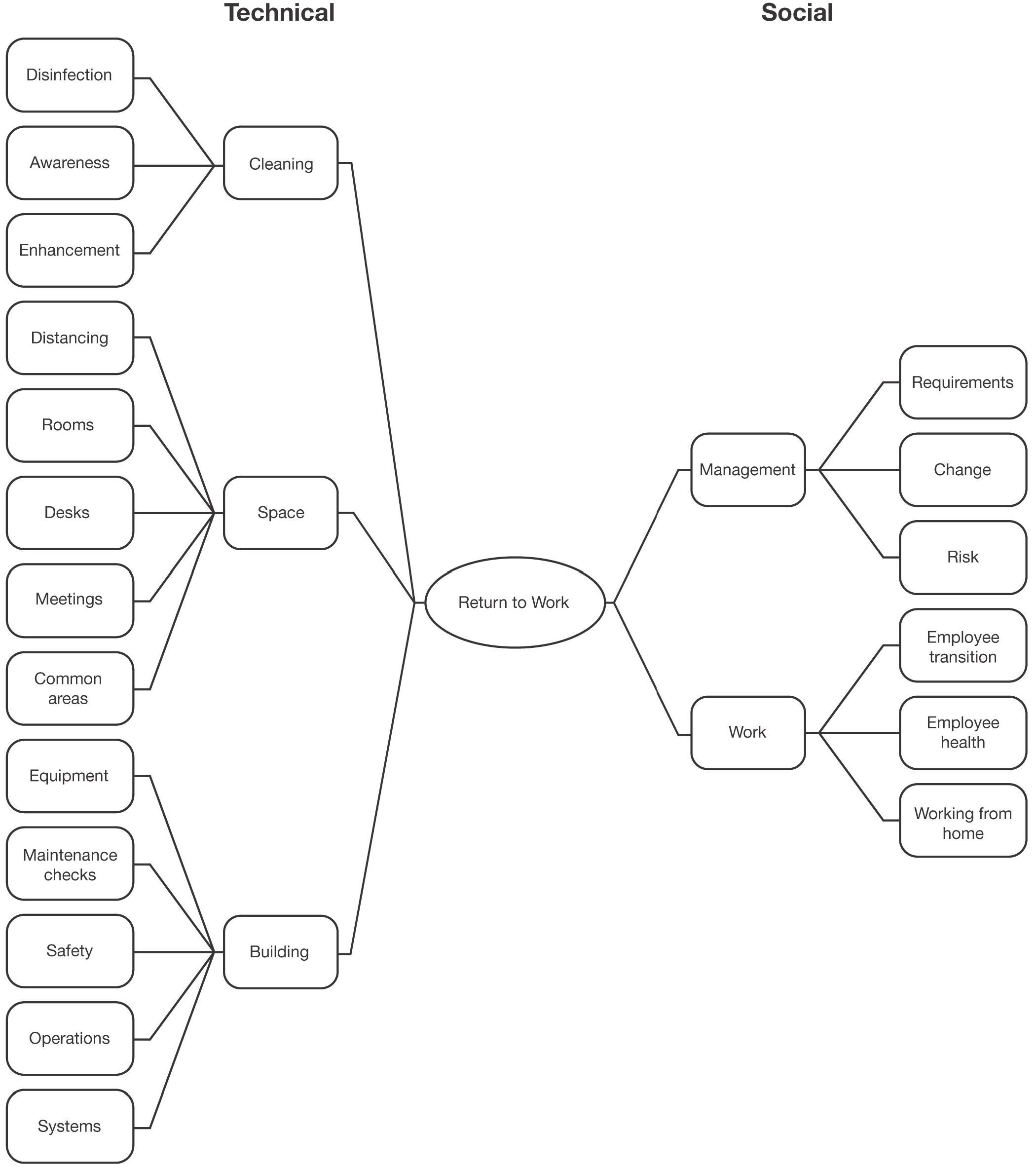

potential for varying sectors and professions to return to work, many CRE and FM providers rapidly developed and issued ‘return-to-work’ guidance. A thematic analysis of eight ‘return-to-work guides’ (see Figure 1) produced during the initial weeks of the UK epidemic shows that five overall themes dominated: buildings (physical space, systems, equipment); cleaning (enhanced disinfection methods and standards); workspace (distancing and density); management (change management, risk); and work (points regarding employee transitions).

6

6

7

7

8

8

Similar guidance has been issued in other countries too, for example in the US,Australia and Canada.

9

9

10

10

Making the qualitative distinction between workspace (as physical) and workplace (as social), it is clear that such guides tend to focus on the built environment and the configuration of the workspace within it, rather than truly helping organisations navigate the wider challenges of work and workplace. They typically ignore or avoid questions relating to the future of work and how best to support it. For example, in contrast to the granular detail regarding an organisation’s physical space, there was scant consideration of cultural and technological elements, both key to organisational performance.

11

11

12

12

Considering workplace as a necessary (and inevitable) interplay between the social (cultural) and the technical (spatial and technological), workplace can be conceived as a socio-technical system. This concept was introduced in the 1950s as a way to better understand the complexities of organisational performance in a systemic way. Seminal studies from the Tavistock Instituteexamining productivity in workplaces identified that the interactions within social and technical systems contribute to work outcomes. This early work revealed the necessity of considering both the technical system (processes, tasks and technologies) and the social system (workgroup attributes and the authority structures. A focus on

13

13

one can ultimately be detrimental to the performance of the system overall.

14

14

In this current situation, the early industry responses to COVID-19 appear to be focused predominantly on the technical. There are likely to be a range of reasons for this but — echoing the lessons from systems thinking — dominating technical factors should not be at the expense of considering the needs of the employees and how best to support them.

Put more simply, while clearly practically useful, such guidance may have missed a patent opportunity in that it focuses on how to get people back into buildings, rather than encouraging the genuine consideration of whether they need to be there in the first place, and why.

BEYOND WORKSPACE

For some, this focus has created frustration with an industry that fails to recognise that the balance has shifted, perhaps irrevocably, between corporate, home and other ‘third’ spaces. Accepting and embracing this perspective would require organisa-tional workplace strategies and operational approaches to become more accommodating and holistic, not just in service of corporate buildings.

Some organisations have already publicly declared their intentions regarding different approaches to work and therefore their corporate accommodation. For instance, Canada-based online retailer Shopify’s CEO announced:

15

15

’Until recently, work happened in the office. We’ve always had some people remote, but they used the internet as a bridge to the office. This will reverse now.’

Facebook has already announced that it would support remote working for those employees who could until the end of 2020,

Figure 1: Thematic analysis of recent return-to-work guidance documents Source: Tucker & Wilson

16

16

17

17

regardless of lockdown protocols, with sites being reopened at 25 per cent capacity in the meantime for those who need to be on-site. Facebook also recently revealed footage of its augmented office environment using mixed-reality technology (a combination of digital and physical environments).Clearly, for many in the technology sector, the commercial opportunity of the pandemic has not been wasted.

18

18

19

19

These examples potentially represent the extreme in a spectrum of potential responses, particularly as both are digital organisations applying similar principles to their working environments as they do to their customer interfaces. There are, however, other sectors also suggesting change is afoot. Barclays’ CEO became one of the first leaders of a major brand to provide critique on occupation strategies, suggesting that big city centre offices ‘may be a thing of the past’.Although perhaps not to the extreme as digital giants such as Shopify and Facebook, Barclays could have some property agencies looking nervously over their shoulder and indicate why some have predicted difficult times for the sector.

ENABLING WORK

The discourse playing out in the news and on social media appears centred around a single binary choice: work from home or work in the office (clearly, this is also a relative luxury in a pandemic for organisations and business sectors where homeworking is possible). Again, this has frustrated some, particularly those who embrace the holistic implications of workplace management.

20

20

Such workplace advocates might suggest the answer is not simply to reduce, or remove, corporate spaces and expect a workforce to work from home. Until December 2019 only around 30 per cent of the UK workforce had ever worked from home,implying some 23.9m people were asked to do it for the first time as the lockdown

21

21

was announced. Data gathered in the US in 2019 suggested that only 7 per cent of private sector workers and 4 per cent of public sector workers were allowed to ‘telework’. Inevitably, the sudden move to homeworking en masse has therefore had mixed results.

22

22

23

23

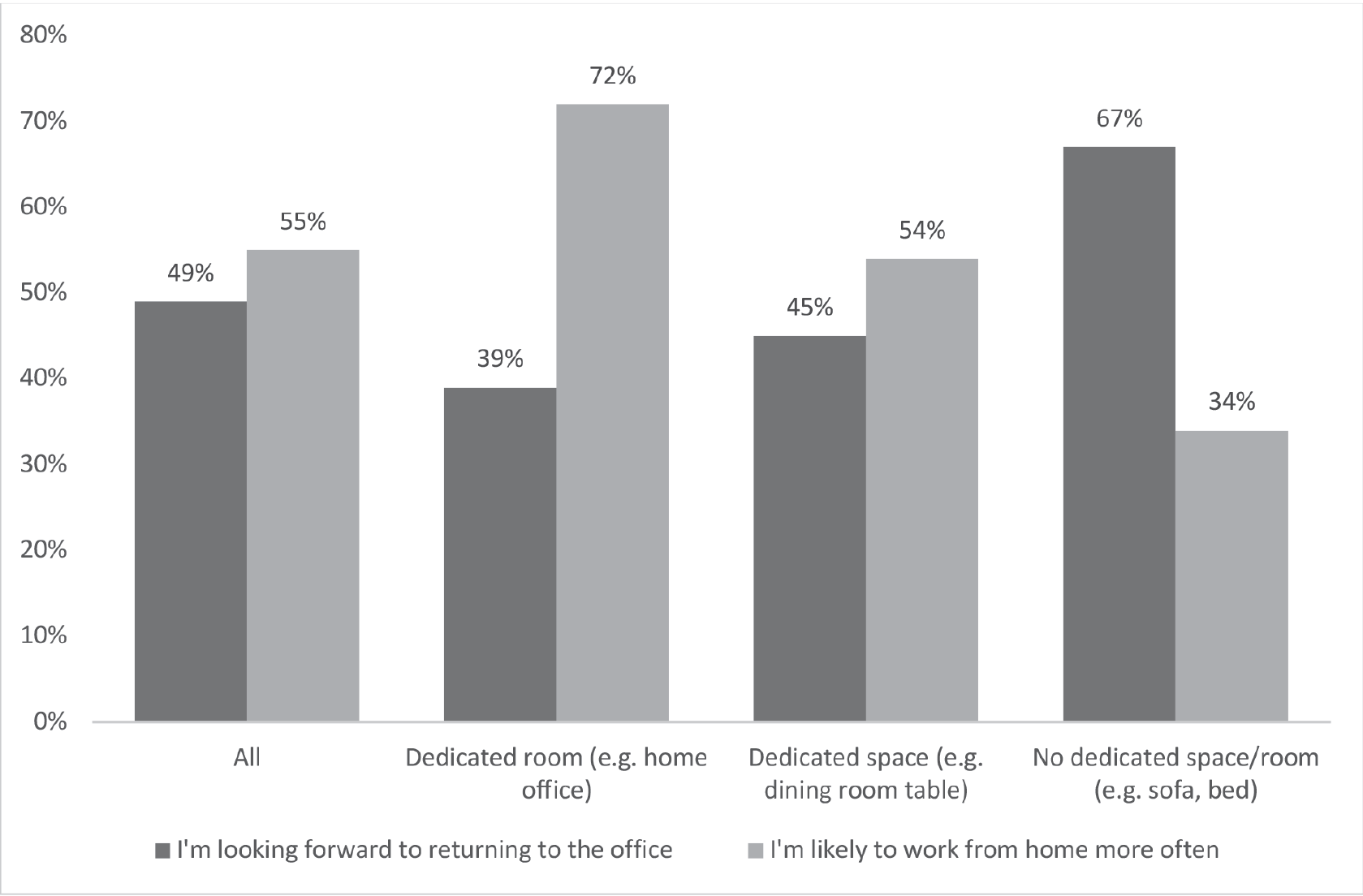

According to other recent data from the UK, 49 per cent of workers are looking forward to getting back into the office, while 55 per cent agreed that this period has encouraged them to work from home more often post-lockdown. These figures are also reflected in data collected elsewhere. For instance, a survey of workers in the US in March and April 2020 revealed that 59 per cent of people would like to work remotely as much as possible once COVID-19 restrictions have been lifted, with 41 per cent of people preferring to work in the office as much as they previously did.

24

24

In the case of the UK data, one of the key differences between whether or not workers are looking forward to getting back into the office seems to be their homework settings (see Figure 2), with those that have access to a home office workspace, a quarter of respondents, stating they are more likely to work from home in the future (72 per cent) and less likely to be looking forward to going back to the office (39 per cent).

25

25

26

26

In stark contrast, for the 15 per cent of respondents who are not working in a dedicated home workspace (for example, from a sofa or a bed) this pattern inverts, with respondents much less likely to want to work from home (34 per cent) and subsequently much more positive in terms of wanting to return to the office (67 per cent). Between these two groups, almost half of respondents (49 per cent) report a dedicated home workspace but no office (for instance, a dining room or kitchen table). Of these, 54 per cent state that they are likely to work from home more often and 45 per cent are looking forward to returning to the office.

Consequently, as organisations offer

guidance to those assessing how they get employees back into their corporate workspaces, the question that may be more appropriate is not how, but who. The data suggests far more nuanced implications for different social demographics and geographical areas than have previously been recognised by the industry. Again, from a socio-technical workplace perspective, the impacts may be complex and significant.

27

27

Asking questions about who needs to return and who might not be able to return requires careful deliberation. In some cases, it may be clear who should make up the initial wave of re-entry, but there are many factors that need consideration when inviting employees back into the workspace. These include, for example, employees’ ability to continue working from home, organisational factors and, not least, the medical profile of staff, but thus far such awareness and guidance appears to be in short industry supply.

Echoing the dominant binary discourse

of home or work, two major groups have been identified in the post-pandemic workforce: on-site employees and those who may not come back to site. In reality, on-site employees actually belie several subgroups: those who never left, those who will be first to return by necessity, and then remaining employees who will return in a steady flow over time. These groups will all require a unique set of adjustments in the way they work. For this to transpire successfully, employees must, above all, feel safe to return to the workplace.

This apparent lack of depth to the ‘return-to-work’ debate, it could be argued, points to a gap in the organisational structure: a role responsible for the workplace experience regardless of where it takes place — one that transcends property strategies or FM service operations and, instead of looking at the space implications of post-lockdown reoccupation, considers what future employee experience looks like in the coming months

Figure 2: Preferences to continue working from home post-lockdown Source: Moriarty

and years, beyond as well as within a traditional organisational workspace remit.

28

28

This is reflected in further data from the same homeworking study. When employees were asked what they were looking for from their employers to support better homeworking in the future, help in creating a productive working environment came out with the most agreement (30 per cent). This was ahead of better IT support (24 per cent) and clearer flexible working policies (20 per cent). The challenge, it seems, is it is unclear in organisations who would be responsible for such a remit. If it were FM, or another member of the built environment fraternity, would the focus remain on the technical (for example, health and safety and compliance) rather than the socio-technical workplace opportunity to systemically enable productive work?

29

29

30

30

There is evidence, however, that FM is beginning to recognise the need for a role that goes beyond physical organisational workspace. For example, recent research indicates that some FMs see their role as ‘enabling people to work wherever they need to’, rather than ‘managing the spaces where people work’. This suggests a future-focused recognition of what can be evidenced as some of the earliest foundations of the FM profession.

EXPERT WORKPLACE MANAGEMENT

31

31

The impact that a workplace can have on organisational performance has previously been expressed many times. One such recent account advocated for the role of chief workplace officer (CWO) in response to the challenge of ownership within the organisation. This new, holistic role (or at the very least, awareness in principle) within organi-sations would act as a ‘super-connector’ that combined CRE, human resources (HR), IT and FM organisational functions. For a number of years different ‘tribes’ within the built environment have extolled the role of

the workplace concept, albeit in line with their primary physical workspace focus. This of course risks restricting workplace matters to the technical sphere of thinking.

32

32

33

33

An early definition of FM as ‘expert workplace management’ has the closest affinity with how workplace has been positioned in this paper. This is further evidenced in isolated past articles charting either FM’s history or proposed futures at the time, with FM being described during the 1990s as ‘a belief in potential to improve processes by which workplaces can be managed to inspire people to give their best, to support their effectiveness and ultimately to make a positive contribution to economic growth and organizational success’.

34

34

35

35

During the 2000s the focus on a holistic notion of workplace was still present, succinctly defined as ‘the integrated management of the workplace to enhance performance of the organisation’. In this definition, ‘integrated’ came from the authors’ work to codify various definitions and distil them down into the various aspects of workplace management (see Figure 3) that were considered key issues. These are still key considerations for organisations today, but many of these decisions will not be within the remit of the FM department.

36

36

The only aspects that date these early descriptions is the preoccupation with the physical organisational workspace, but at the time flexible working was only beginning to receive attention. This preoccupation may go some way to explain the focus in today’s ‘return-to-work’ guides.

37

37

38

38

But the concept of integration perhaps points to why workplace strategy continues to be regarded as a subset of other professional disciplines. It has been highlighted that FM requires multiple skill sets, which results in an array of professional disciplines coming together, and it was suggested that each of these professional disciplines attempt to promote its own body of opinion. It has been recognised that while it is important to

Figure 3: Key issues in FM Source: Tay and Ooi

39

39

recognise these professions, and their contribution, within this function, it is equally important to recognise the need for an overall strategic approach.

DO NOT WASTE A GOOD CRISIS

40

40

The FM community, like many professions, often calls for a presence in the boardroom. The reality is, however, that outside of financial roles, the structure of a board will depend largely on the structure and mindset of the organisation. A seat is not a given right; it must demonstrate business value and be contextually relevant. This desire to be in the boardroom is closely related to the commonly heard assertion that ‘FM needs to be more strategic’, which seems more about relative importance than long-term strategic planning per se. It reflects an industry that seeks recognition as a value contributor, in order to move away from commoditisation — the tragedy of the commons that has befallen it over the years — and a professional community that wants more recognition for its contribution within organisations.

It was the combination of these ideas — the growing interest from organisations in

workplace matters and FM’s desire for more strategic relevance — that sat behind the British Institute of Facilities Management (BIFM) repositioning as the Institute of Workplace and Facilities Management (IWFM), in recognition of the headline socio-technical importance of the workplace, not as a subset of something else.

The reality is that change will only come about because of actions rather than words alone. Rather than just talking about being different, the profession needs to be different, and this will mean individual facilities managers acting differently. This will inevitably be uncomfortable and challenging, because almost all change requires additional effort and resource.

41

41

One action is to start thinking more holistically about the workplace and how FM operations (whether outsourced or not) can enable it. Rather than seeing workplace purely in physical terms, FMs need to understand the sometimes subtle relationships between the spatial, cultural and technological aspects of workplace — and how these relate to the needs of the organi-sations those workplaces support.

To think about workplace in these socio-technical terms requires new competencies — ones that combine behavioural sciences alongside technical expertise; cultural and digital competences, in addition to spatial ones. To demonstrate broader relevance and impact to organisations, the ways in which workplace impacts are measured must develop beyond an intrinsic property/finan-cial focus toward the ability to support individual and organisational performance. Such metrics that are currently more closely aligned with and more likely to sit within a HR function.

Indeed, HR provides an example for how a profession can seek to reposition itself, with a view to becoming more business-relevant and ensuring it remains fit for the future. In 2018, the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) launched its New

Profession Map, which included capabilities such as analytics and ‘creating value’. It has also taken to describing itself as the ‘people profession’, thereby placing people at the centre of what the profession is about.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the critical role that today’s FMs, and built environment industry professionals more generally, can play in organisations beyond ‘keeping the lights on’ during lockdown and helping people return to organisational workspaces safely and stay healthy during recovery. These contributions are clearly vitally important, but as organisations cautiously explore what a new ‘normal’ might look like as they try and make sense of the post-pandemic world, there is an opportunity for a new socio-technically aware profession, inspired by a formative conception of workplace that has been there all along, to emerge and to contribute proactively to discussions about the future world of work.

Such discussions need to be underpinned by robust research into how people’s relationships with work and the workplace have been affected by the COVID-19 homeworking ‘experiment’, and the degree to which these changes signify a temporary modification or a more enduring shift to the world of work. Most of the research conducted during the pandemic has taken the form of ‘headline-grabbing’ surveys, which, while useful, tend to focus on the what rather than the why. Future research in this area could therefore seek to develop a much richer picture of workers’ attitudes and lived experiences and explore what implications these will have for the future of workplace.

references

- McGregor, W. (2000), ‘The future of workspace management’, Facilities, Vol. 18, Nos. 3/4, pp. 138–143.

- Trist, E. L. and Bamforth, K. W. (1951), ‘Some social and psychological

- consequences of the longwall method of coal-getting: An examination of the psychological situation and defences of a work group in relation to the social structure and technological content of the work system’, Human Relations, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 3–38.

- Price, I. (2003), ‘Facility management as an emerging discipline’, in Best, R., Langston, C. and De Valence G. (eds), Workplace Strategies and Facilities Management, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, pp. 30–48.

- Pinder, J. and Ellison, I. (2018), ‘Managing facilities or enabling communities? Embracing culture to move FM forwards’, IWFM, available at https:// www.iwfm.org.uk/resource/culture-report.html (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Tucker, M. and Wilson, H. (2020), ‘Return to Work Guides – A Thematic Analysis’, Facilitate Magazine, available at https://www.facilitatemagazine.com/ (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Moura, S. (2020), ‘Navigating a Safe Return to Work: Best Practices for U.S. Office Building Owners and Tenants’, NAIOP, available at https://www.naiop. org/en/Research-and-Publications/ Reports/Navigating-a-Safe-Return-to-Work-Best-Practices-for-US-Office-Building-Owners-and-Tenants (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- JLL (2020), ‘COVID-19: Top 10 focus areas for workplace re-entry checklist’, available at https://www.jll.com.au/en/ views/covid19-top-10-focus-areas-for-workplace-re-entry (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Colliers (2020), ‘Way Forward >> Together: A Practical Back-to-Business Primer for Occupiers/Tenants & Investors/Landlords’, Colliers, available at https://www.collierscanada.com/en-ca/ services/back-to-office-guide (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Pinder, J. and Ellison, I. (2018), ‘The workplace paradigm: embracing workplace to move FM forward’, IWFM, available at https://www.iwfm.org. uk/resource/the-workplace-paradigm.

html?parentId=EB5ABB65-B258-4F32964F8CB5151B673E (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Ibid., note 9.

- Ibid., note 2.

- Appelbaum, S. H. (1997), ‘Socio-technical systems theory: An intervention strategy for organizational development’, Management Decision, Vol. 35, No. 6, pp. 452–463.

- Ibid., note 2.

- Mumford, E. (2006), ‘The story of socio-technical design: Reflections on its successes, failures and potential’, Information Systems Journal, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 317–342.

- Targett, E. (2020), ‘Shopify CEO: The Office is Dead. 2020’, Computer Business Review, available at https://www. cbronline.com/news/shopify-office-is-dead (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Gurman, M. and Wagner, K. (2020), ‘Facebook to Limit Offices to 25% Capacity, Require Masks at Work’, Bloomberg, available at https://www. bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-05-20/ facebook-to-limit-offices-to-25-capacity-require-masks-at-work (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Inquirer.net (2020), ‘Facebook’s remote workers of the future could work in AR-powered virtual offices’, available at https://technology.inquirer.net/99911/ facebooks-remote-workers-of-the-future-could-work-in-ar-powered-virtual-offices (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- BBC (2020), ‘Barclays boss: Big offices may be a thing of the past’, available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/ business-52467965 (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Sheetz, M. (2020), ‘Icahn is shorting the commercial real estate market, which he says is going to “blow up”’, CNBC, available at https://www.cnbc. com/2020/03/13/icahn-reveals-his-biggest-short-position-amid-market-turmoil-commercial-real-estate.html (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- ONS (2020), ‘Coronavirus and homeworking in the UK labour market: 2019’, Office for National

- Statistics, available at https://www.ons. gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/ peopleinwork/employmentandemployee types/articles/coronavirusandhomeworking intheuklabourmarket/2019 (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Desilver, D. (2020), ‘Working from home was a luxury for the relatively affluent before coronavirus – not any more’, World Economic Forum, available at https:// www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/ working-from-home-coronavirus-workers-future-of-work/ (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- IWFM (2020)’, ‘COVID-19 guidance: Returning to work, available at https:// www.iwfm.org.uk/coronavirus-resources/ covid-19-guidance-returning-to-work. html#IWFM%20YouGov%20research%20 COVID-19 (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Brenan, M. (2020), ‘U.S. Workers Discovering Affinity for Remote Work’, Gallup, available at https://news.gallup. com/poll/306695/workers-discovering-affinity-remote-work.aspx (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Moriarty C. (2020), ‘Industry Perspective [Internet]: Intelligent Buildings Europe’, IFSEC Global podcast, available at https:// www.ifsecglobal.com/ibe-digital-week/ (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Ibid., note 25.

- Ibid., note 25.

- Korn Ferry (2020), ‘Accelerating through the turn: Preparing for a future beyond the crisis’, available at https://www. kornferry.com/challenges/recovery (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Ibid., note 23.

- Ibid., note 9.

- Ibid., note 3.

- The Stoddart Review (2016), ‘The Workplace Advantage 2016’, available at ()https://stoddartreview.com/ (accessed 16th July, 2020).

- Ibid., note 3.

- Alexander, K. A. (1994), ‘Strategy for facilities management’, Facilities, Vol. 12, No. 11, pp. 6–10.

- Tay, L. and Ooi, J. T. L. (2001), ‘Facilities management: A “Jack of all trades”?’, Facilities, Vol. 19, No. 10, pp. 357–363.

- Ibid., note 36.

- Cairns, G. and Beech, N. (1999), ‘Flexible working: Organisational liberation or individual strait-jacket?’, Facilities, Vol. 17, Nos. 1/2, pp. 18–23.

- Ibid., note 36.

- Quah, L. K. (1999), ‘Facilities Management and Maintenance: The Way Ahead Into the Millennium: Proceedings

- of the International Symposium on Management, Maintenance and Modernisation of Buildings Facilities, 18th–20th November 1998’, McGraw-Hill, Singapore.

- Ibid., note 35.

- Ibid., note 4.

- Ibid., note 9.